“But we’ve always done it this way.” There is comfort in the familiar. We have built our expertise and understanding around the way things are; our “mental models”, our personal, internal representations of external reality that we use to interact with the world around us, are different from person to person. Each of our mental models is constructed based on our unique life experiences, perceptions, and understandings of the world. Everyone has a mental model of education that they bring to the table when discussing education reform. We face the uncomfortable disconnect between stakeholders who simultaneously want “better”, but don’t really want things to change from what they are used to. We want schools to get better results, but they shouldn’t fundamentally change from what we already believe about what schools should be.

These mental models create a set of basic assumptions within our unconscious behaviors that guide us on how to perceive, think about, and feel about things that are extremely difficult to change. To rewire this requires us to “resurrect, reexamine, and possibly change some of the more stable portions of our cognitive structure. Such learning is intrinsically difficult because the reexamination of basic assumptions temporarily destabilizes our cognitive and interpersonal world, releasing large quantities of basic anxiety.” (Schein, Edgar. 2010. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 4th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.) There is a strong human need for stability and consistency especially in the face of dynamic and uncertain work environments. (Like quitting smoking, a diet… these are hard and humans are often advised not to try these changes if their environment is uncertain.) Schools could not be more dynamic and uncertain.

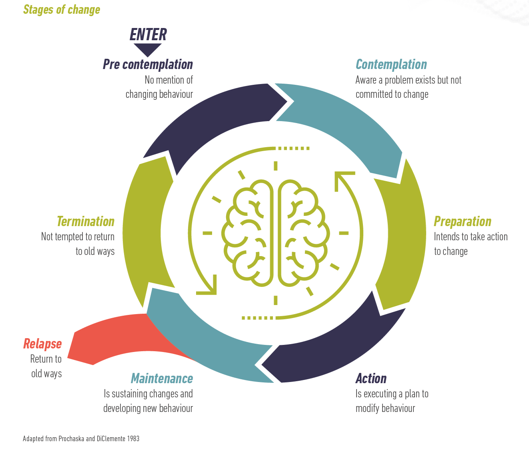

Transformational change is one that fundamentally shifts how we do things; true transformational change requires non-closure, and living in disequilibrium. As with most things, every human handles change differently. Some embrace change, while others avoid it completely. In a system like public schooling, which includes such a large group of stakeholders, we see every possible response to change. People in general avoid the feeling of confusion and disequilibrium; it makes us feel overwhelmed, no longer able to think logically, making us want to simply avoid, then remove ourselves from the situation and revert to comfort.

Consider the analogy of a butterfly inside its cocoon. When you see the butterfly struggling, you are tempted to peel the cocoon off to free the butterfly so that it can fly away. But what happens to a butterfly when it does not have the necessary struggle to free itself from its cocoon? Its wings are weak. The butterfly soon dies. The struggle is what makes the butterfly strong. In a misguided attempt to help it, we destroy it.

We can also consider the lobster; as a lobster grows, its shell becomes confining and the lobster feels uncomfortable and under pressure. It goes under a rocky shelf to protect itself, casts off its shell and produces a new one, risking its life by losing its protective exoskeleton. It repeats this several times throughout its life. The stimulus for the lobster to grow is that it feels uncomfortable. Times of stress are signals for growth. The old way of being, thinking or acting is not working any more and we need to change something. But if we are not willing to feel uncomfortable, we will not change, and we will suffer from chronic stress and be thwarted in our growth. Moreover, for the lobster to grow, it must make itself vulnerable. When it first emerges from the old shell, its new shell is soft and offers little protection. It takes many hours for its new shell to harden. Just like the lobster, both stress and vulnerability are key ingredients for our growth.

Because every part of us generally prefers to avoid struggle and vulnerability, we are drawn back to what we know and are comfortable with, even when we know it isn’t fundamentally doing what we need. We want to hide under that rocky shelf!

We must also consider the importance of sustainable, transformational change (long-lasting, enduring, manageable to maintain without exhausting resources) to address the fundamental issues with our current system. Things change dramatically in a short amount of time in schools and school districts including changes in federal, state, and local funding, which happen regularly, legislation that changes not only yearly, but often during the year (see our 2nd blog post regarding mandated units of study), new school board members are elected every two years, just to name a few. And, as we mentioned, there are also forces that push against any significant change. When we are unable to depend on consistent funding, the ever-changing state and federal requirements, and the ever-changing governance from our school boards, sustainability is incredibly difficult. CEC specifically addresses these barriers in our efforts to support collective solutions and innovations in schools.

Schein [1] advises that to make any substantial change to an organizational culture there needs to be the following present:

- Enough data to cause discomfort and disequilibrium

- The connection between the data and important goals and ideals

- Enough psychological safety to learn something new without loss of identity or integrity

The transformative change required of school staff and society will require both unlearning something while also rewiring our unconscious behaviors. The recent pandemic forced a few examples of this rewiring. Schools, however, are simply not effectively designed to provide a supportive environment for frequent transformation efforts.

- Annual staff and leadership turnover creates inconsistency and discomfort in group membership/identity

- Important goals and targets are adjusted quickly and before full implementation is realized

- Competitive relationships and perceptions (internal and external) reduce risk-taking and learning

- Time is not provided to test and try out new behaviors thoroughly and without disrupting default

- A lack of positive examples and formal support structures to make significant changes

- Federal changes and mandates (from the Department of Education) and the State Department of Education often occur quickly, with minimal guidance, and no financial support for implementation.

Even when school systems have found opportunities to break through all of the rewiring mentioned above, our society still encourages the system to stay put. (See one example HERE.) While there is pressure to innovate and evolve there is equal counterpressure to remain exactly the same. Let’s consider the issues surrounding one minor change: altering the school day start time for 9-12th graders. Research is clear; teens would academically benefit from later start times. A quick search of the internet will produce numerous examples of school systems attempting to make research-based innovations around starting times for teens and then being pressured to return to earlier start times by the community. The reasons? Generally, these debates are about parent working hours, sports, or teens after-school responsibilities like work or babysitting younger siblings. Attempts at even basic innovations like altering length of the school day, number of days in attendance, months when schooling takes place (to name a few) are met with such strong opposition from society that schools often abandon the effort despite having solid research that these changes could make needed academic progress for students. It would require, however, society to adjust and change along with the schools. The full school community would need to evolve. We need to decide if we are a learning organization or a childcare organization; while parents need both, schools cannot evolve if we are also expected to be childcare providers.

Structural changes in schools are easy. Cultural and behavioral changes are not. In supporting and advocating for innovation or transformation in our schools, consider all of the stages of change required. Similar to the issues with quitting smoking or diets, don’t make unreasonable demands for quick improvements that likely do not last long or result in future deficiencies.

Addressing the issues that contribute to making quality transformation is foundational to bringing all of the Six Boundaries together in forward movement. Innovation in school can happen when school staff, school management, and the wider school community are all in alignment. A few public, charter, and private schools have been highly successful in these types of transformations. Our schools at-large, however, have not. CEC knows that the system context and attention to change management practices are the differentiator in truly innovating.

We encourage you to consider the following:

- To what extent are you willing to live in disequilibrium to make effective, systemic, systemized changes to how we do school?

- What unlearning can you engage in as you consider how we transform schools?

- How can we work together to fight that gravitational pull back to “the way we always do it”?

- What is the role of change management practices in reaching your school’s innovative aspirations?